Ernesto Leal’s work and thinking always bring back up in me the passion of mulling over art as the ideal space to “invent” our lives from an unbiased and diversified perspective, especially now when this term is increasingly catching on as a palliative in the face of global skepticism. So imaginative and scathing, he reminds me of the Sade Marquis’ philosophy and his “limits experience.” Maybe I noticed this for the first time in his Civilians in Shock exhibit, when I was talking with Piña about the weakening of utopia from within itself. Leal’s work carries a de-echeloning gesture that calls into question such issues as Art History and its logo-centric vision of the discourse, the aura tradition over the artistic development, its alleged socio-cultural outreach and any expression of power that breaks free from individual freedom.

Those who know Ernesto are aware he’s not an ordinary guy. He’s sometimes short on words, and some other times he’s very outspoken. He’s been called dense and I agree with that. The fact that some or many see density in his work has to do with the artist’s illustrated thoughts –just to give a name of sorts to his acute reflections– and the seriousness he tackles his answers with, let alone the hours he spends reading and doing research. The latter is way too obvious because it can be seen to a naked eye. Perhaps if I were to represent him, I’d put halfway between the mystic and the scientific. His big break in the artistic scene came to pass during the hot 1980s and from that moment on his works have always been concerned about homing in on the artistic discourse and its cultural connotations, but not under a thin skin, but rather unraveling the wisdom and the breaches, unearthing like a good archeologist or not the roots of our knowledge, of our tremendous ability to apprehend what is construed as “real” by us. At the same time, we make reference to the intelligentsia of his works and the artist wonders: Are Cubans engaged in a postmodern context? Is this talk about between-the-lines readings legit just because it leans to being related to the post era?

In 1997, the artist went to the Teodoro Ramos Blanco Gallery in the municipality of Cerro, in the city of Havana, with an exhibit he called Ernesto Leal and that consisted of a change of meanings by placing the Barbara Gladstone Gallery lettering in the façade of the Havana institution and a second lettering reading “Real” inside the gallery, right on the walls. According to Leal, “with this I intended to make good on the intercrossing of spaces by means of name smuggling,” and he named after them just to lampoon the strategy he had used.

One of the artist’s features is his refusal to have his work pigeonholed in a particular trend, theme or technique. He’s not interested in that labeling at all because he just disbelieves everything. Back in the year 2000, he exhibited Guided Tour, a series of photographs mounted on wheels that simultaneously document the author’s Havana house and the Air Museum, a state-run institution devoted to the history of aviation in Cuba. According to the author himself, the piece is “a fictitious visit to two places at the same time in which there’s an intention to make a fuss about the brittle borderlines between the inner and the outer spaces in a framework in which culture is seen as a museum-related value, closed and unaltered, rather than as an ever-growing, ever-building process”. This proposal was exhibited at the Istanbul Biennial in Turkey, as well as in Berlin and New York.

When I met Ernesto personally in 2001, during his Civilians in Shock exposition at the Havana Gallery, together with the unforgettable Manuel Piña in tow, I knew I had a genuine artists right before my eyes; not the ones trained by Salamanca, but those Nature begets. The proposal at that time dealt with utopia and the impossibility of carrying it through as a consequence of extreme apathy, lack of initiative, censorship and self-imposed censorship. But all that much was addressed with high levels of assorted tropes.

Two great ones making great metaphors that, as a result of their grandeur, went nearly unnoticed regardless of the great exhibit that was. Those were times when that institution was painstakingly showcasing interesting artists and projects. Photography, videos, light boxes and embossed paper were the resources used by the artist for his reflections in that controversial context. Three pieces from that exhibition were displayed under the general title of Higher Institute of Double Agents.

Leal is concerned with everything that affects individuality, both publicly and privately. Perhaps that explains why his reflections are sometimes penciled in as intimate, but nothing can be farther from the truth. This is what actually happens: his exercises remind us of certain physical experiments that could render in the levels of relativity, as if it were an attempt to try to represent the many layers of reality we usually interrelate with. His intentions have to do with the dismantling of unilateral notions that could thwart full understanding of the developments, either social or cultural ones. And he has managed to come by this much through a discourse of his own that sometimes looks so airtight because it precisely deals with levels of intention and interpretation of the “real”. Every so often people only get to see the appearance of the processes and never look into their origins, their possibilities and consequences.

Standing up for free self-determination seems to be one of topics broached in Free Vacant Lots, 2004, a video installation that, together with two other pieces, makes up a series in which planet Mars is taken as a reference to speak about cultural belongingness and the notion of homeland. It consists of a video presentation on the floor with a sequence of vacant lots on planet Mars. The projection creates the appearance of diluted territories since none of the fragments holds its own shape for too long. On the four sides of the video, spectators can read: Free Vacant Lots and Homeland Creation Banned. Once again, Ernesto boasts his sarcasm and gives us his version of freedom stacked up against the essentialist and branded notions that only manage to cut down on the homeland concept.

The 9th Habana Biennial brought the second piece of this exhibit at the National Museum of Fine Arts building: A New Homeland to Rest. It consisted of a video presentation in which the author was shown doing a juridical operation in the presence of a notary just to donate vacant lots on Mars to the Colon Cemetery in Havana (a acre) that had been previously bought by him from Denis Hoper on the Internet (a property acquired on www.Marshop.com The Lunar Embassy 1506 Hwy 395 Gardnerville, NV 89410).

Arbitrary manipulations have been time and again been in the artist’s best interest when it comes to his proposals. On a gallery wall, he’s put ribbons with vinyl letterings and a small monitor showing a video loop. The latter underscores the uses of ellipsis or dots in literature. The piece entitled Deleted Fragment, 2005, intends to lampoon the use of ellipsis when an author uses another author’s quotation in line with his or her personal ends. By doing so, Ernesto tries to strike people’s attention on the margins of arbitrariness that might hide behind any quotation or text we read, as well as on how somebody can have a call on what should or should not be shown, depending on what the interests dictate. The video image consists of an exercise in which several of the sign’s possibilities show up and its structure is transformed into a decorative image. The more its look change, the more ambiguous it becomes, thus enhancing its quite unmasked meaningfulness. I like this piece a good deal because I hate to see quotations in critical texts, unless they are strictly necessary. Most of the time it looks like an appropriate filler to conceal other weaknesses, lest it were an attempt to just dazzle people.

In an effort to track down the most significant examples of the plastic arts on the island nation, the 5th Exhibition of Cuban Contemporary Art showcased Cracks, a piece based on the representation of thin lines on a strip of paper that had resulted from the spaces between words in certain texts. The artist took pages from several books and highlighted the blank spaces in each and every one of them. Then he dotted those spaces with a pencil to evoke cracks or gaps and demonstrate the shortcomings and flaw that any text can actually hide.

Playing with the spic character of a considerable chunk of Cuban photography is seen in the fourteen pictures that make up Neither Here II, 2008. In the first part of the series, the artist worked on private spaces, but this time around he zeroes in on art spaces (Cuban art galleries and museums) like the Center for Visual Arts Development (CDAV), La Casona Gallery, Havana Gallery, the Museum of Fine Arts, in a bid to switch the epic notion within the framework of overall culture. And he chooses to take pictures of apparently unnoticed and poorly-revealing corners and places just to make them look as icons of locations that can hide both glory and grandeur, from his own viewpoint.

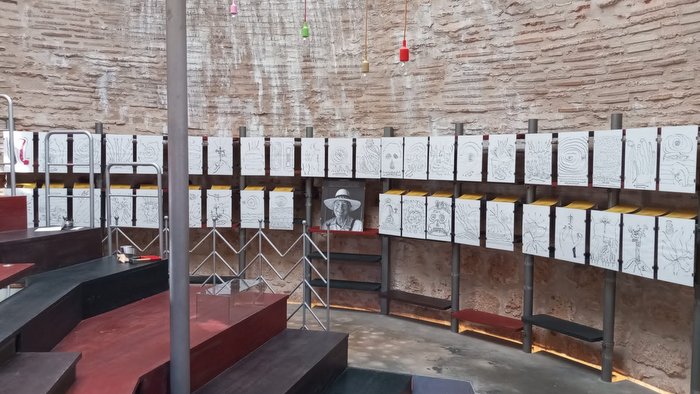

Quite recently, between May and June 2009, the Havana Gallery exposed his personal exhibit entitled Language Disorders, a sort of environment or intervention that comments, among other things, on the meditations that twist the true dimension of the artistic message, though given his traditional ripple effects, the intention happens to engulf any kind of message.

It took him roughly a year to conciliate with half a dozen art critics the same amount of texts by handing over a description to each of them by means of gallery sketches, diagrams and blueprints for the six pieces that included installations, video installations and photographs. And he exposed the result in the same space and under the same sizes that each piece was supposed to take inside the gallery.

The critics handpicked for the occasion were Corina Matamoros, Elvia Rosa Castro, Cristina Vives, Frency, Magaly Espinosa and Tom Wride, a photography curator with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Just to mention but three instances, for Corina he comes out as a restless person eager to access to as much information as he possibly can just to achieve an in-depth reading of his intentions. Vives speaks from a collector’s standpoint and acts smartly when it comes to taking on the limitations of critique. As far as Elvia is concerned, his approach puts the focus back on philosophy and glosses Leal’s intentions from a syllogism.

The artist engages in virtually everything to wield art review as one of the links of a much longer chain. The creation-circulation-consumption circuit determines the fate of the arts to a large extent, and sometimes institutions carry a heavy weight in that process. That explains why his work has stopped being an autonomous and self-sufficient institution that conditions its final destiny, while the art gallery or museum is no longer the simple and harmless space that guarantees its presence. Can we question the way art galleries selects artists? Can we raise doubts about who are on the auction lists? Sometimes critics or certain powerful institutions are the ones that catapult artists into stardom. Those who don’t meet the requirements established by them are more likely to stay out of the promotion and consumption circuit, at least not in a very efficient way.

In Cuba, information on original works and events from around the world usually come down in a referential manner, by the hands of art students, critics, curators and many times by the artists themselves, and that stems mostly from the existing travel restrictions. The author also wants to make people chew over that inconvenience that quite often can hamstring full-fledged comprehension of the arts within our own context, just when critics engage in the description of the possible artworks, thus establishing an allegory on how those who write or create artworks can sometimes swing at the wrong pitch.

Ernesto has turned critics into accomplices of the meditations that usually hamper access to artworks. Many between-the-lines texts pop up when the exhibits are analyzed and they implicitly include the Babel Tower, Sade, Eco, the variable posts… the crisis of culture, contents on the endless sign. There are subtexts as well: ideological, political, social, philosophical and even religious (reread Cristina Vives’ description). This creation continues to be one of the least forewarned of all, as I wrote in a text I made for this particular exhibit in Artecubano. No wonder that Tim Wride’s comment was posted right at the beginning of the gallery tour. Why has Leal’s work been more exposed overseas than in Cuba? Better yet: why has it been displayed outside first and inside later? As the saying goes, no man is a prophet in his own land, but quality must come through by the hand of imposition. The ambience of the exhibition hints at some uneasiness on our own ability to analyze, goading us into some kind of intellectual setup and leading us into countless questions that remain unanswered: what does his outspoken language actually mean and what are its consequences? How many disorders are we subjected to when we write? But there’s one thing that goes without saying: Leal has put on a hell of a show. He’s now to be taken into account when the moment to write about the history of Cuba’s plastic creation –with its achievements and confusions– finally comes.