Today we’re pulling out three files. They belong to artists who are considered to be both Spanish and Cuban in the same breath. It’s not a riddle, but just the trappings of this complex planet so full of borders, anthems, coats of arms and flags.

The first file belongs to Hipolito Hidalgo de Caviedes (Madrid, 1901-1994), son of the name-like Spanish painter. He came to town in 1936 and the following year he mounted his first personal exhibit at the Architect College in Havana. The first thing that really amazes anyone who delves into his documents is the intense activity this painter had during his stay in Cuba and that stretched till 1961 when he definitely returned to Spain. His murals are everywhere: the lobby of the “Piti Fajardo” Hospital, the Belen College (currently the Military Technical Institute), the Diario de la Marina (Abril Publishing House), the L’Aiglon restaurant at the Riviera Hotel, the Havana Cathedral.

This mural activity also came along the decoration of stores and private homes, illustrations for magazines and portraits. It could then be said that his work lacks esthetic values and that he must be first corralled only to be thrown into oblivion later on. It’s true that his work in Cuba was, generally speaking, kind of only restricted to the artistic ambience. If we look for information on this painter in the newspapers of his days, he made far more showings in the social columns than in those related to the arts. His close ties with the Havana high-life explained away the multitude of works he was commissioned to do, but the undisputed quality of his artworks clearly surpasses any other extra-artistic criterion. Right before our eyes, we have a singular fact: an artist who worked in Cuba for a quarter of a century, yet he’s now recognized in Spain and forgotten in Cuba, the country where he probably carried out the most significant part of his work.

Another name, another situation. The second file belongs to Federico Beltran Masses (Guira de Melena, 1885-Barcelona, 1949), of Cuban father and Spanish mother, who left Cuba with his parents in 1899 at the end of the Spanish colonial rule on the island. His academic formation unfolded in Barcelona and Paris, while his painting owes nothing to his homeland, not even in terms of reference. There’s only one Cuban landscape he painted when he was in his teens.

Some Spanish critics praised him to the utmost, while others labeled him as an artist who produced “outdated and decadent” paintings. His relationship with Cuba is limited to the making of a few portraits of Cubans who lived in Paris or passed by that city. However, a year after his demise, the Havana Lyceum organized a small retrospective mostly made up of his portraits. Social magazine kept tabs on his career and every so often published articles that stood halfway between an art review and a social chronicle. All of them always mentioned an “upcoming visit” by the artist that seemingly never came to pass.

Some 40 years later, the name of Federico Beltran Masses for completely unknown for Cubans. When the National Museum of Fine Arts reopened in the year 2000 following an all-out refurbishment, the new Cuban Art Halls included two of large-format works by an artist that until then only a few people knew he had been born in Cuba.

Last but not least, we have saved for last the most “Cuban” of this trio: Jose Segura Ezquerro (Almeria, 1897-Marianao, Havana, 1963). He lived in Cuba from 1921 till his passing, except for a brief stay in Spain from 1931 to 1935. He died being a Cuban citizen and had a hands-on participation in Cuba’s cultural life. In the case of Segura, it’s important to point out that his work was linked to the Avance magazine generation and, as matter of fact, he was one of the participants in the New Art Exposition that marked the beginning of modern art in Cuba. During that memorable exhibit, he presented an oil called The Little Brown Girl of the Oranges plus three drawings. The works that came later leant to a more commercial kind of art as he broke away from the painters that have led the way in the avant-gardism movement.

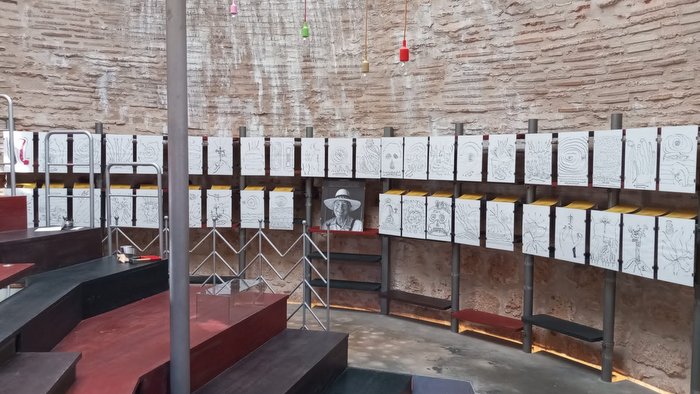

The name of Segura Ezquerro faded away in the memory of the Cuban art until 1988 when curators Ramon Vazquez Diaz and Jose Antonio Navarrete, of the National Museum of Fine Arts, organized the anthological exhibition entitled Avant-gardism: The Emergence of Modern Art in Cuba and in which, among the artists we all wanted to see, the name of Jose Segura Ezquerro popped up. Many discovered an artist; others just remembered then a painter and a drawer who never deserved to be forgotten.

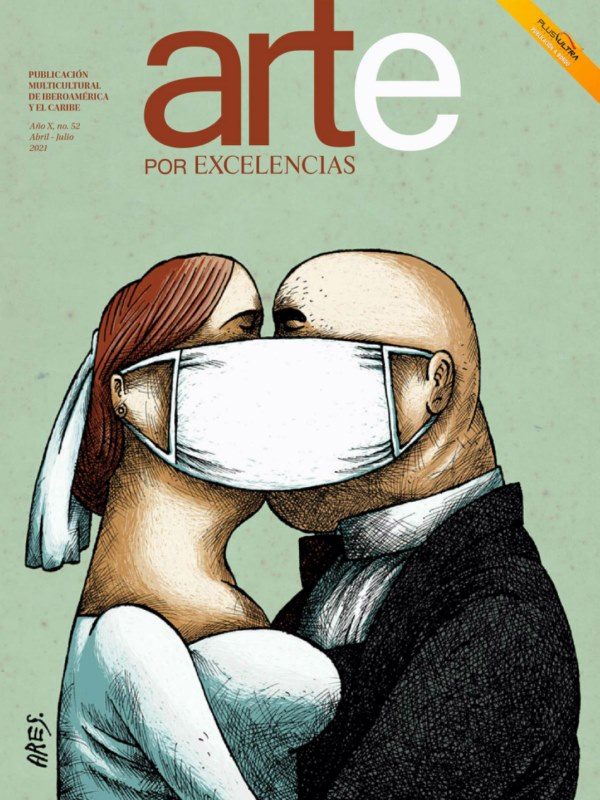

For the fifth issue of the magazine, The Archivist wanted to underscore the close ties that existed and still exist between the Spanish and Cuban arts, but above all, to highlight the need of looking into this quasi-untapped field.

Publicación anterior Tomás Sánchez. Going beyond time

Publicación siguiente NadalitoThe photography of mental processes