From a multitude of approaches, art critics, curators, artists and other experts have homed in on what they call public art, though there’s no such thing as a stamped theoretical definition resulting from the addition of features that qualify the diversity of practices ruled by that category.

However, the issue many theoreticians do seem to agree on is the inclusion in the public art category of a number of proposals that since the 1960s have been whining about the inefficient use of the “white cube” to project new esthetic concerns, coupled with a profound interest in making a kind of public that hardly ever swings by those places where art is displayed or marketed a key player of this artistic development. “This new category is not a style and it evolves regardless of forms, materials and scales,” said Javier Maderuelo (1990: 174), “though it brings together the experiences of the Pop monument, of installations, of architecture, urbanism and other sociological, participative and scenic phenomena.” (Ibidem: 147)

Thus, taking the urban space with its many weaves and wefts as both raw material and interlocutor, the art turns to old and new strategies alike as it singles out and hierarchizes the abstract, the processes, the ludicrous, the mixture of codes coming from heteroclite sources and the new forms of relationships with the receptor and the institution.

One of the somewhat recent approaches on this kind of art leans to a confrontation of it with the logics of both the monument and the spectacle. First of all, contemplating the diversity and complexity of the relationships going on between art and the public space implies to pay heed not only to the linkage between the latter and sculpture, but also to consider a spectrum of artistic creations that fall between two stools in the strict terms of generic classification. According to Felix Duque (2001: 112), “monuments (including squares, gardens and parks) make up a triple way of spacing, of making a public ‘place’ and making a ‘place’ for the public.” In society, those “places” are still on demand, not only amid other urban and citizen dynamics in which the monument becomes nearly invisible and its function boils down to a mere landmark reference.

While today monuments go unnoticed in the middle of so many visual interferences, certain agents try to reach more visibility within the urban environment in their struggles for social, political and ethnic vindications. Nonetheless, “visibility is always related to the possibility of control […] Thus, becoming visible in an urban environment is every so often carried out as an underground activity, through the illegal placing of billboards in the streets, the splaying of graffiti, the broadcasts of pirate radio stations, the emergence of artificial identities on the Internet or a blurry appearance in the middle of a crowd.” (Broeckmann, 2000: 167-169). In its different ways to operate, a considerable chunk of the art going down in the public space shares similar strategies de moving around through a mesh of visibility and invisibility coordinates. A visibility many times achieved by means of action, of a fleeting or camouflaged presence that stands between contingencies and urban instability. An invisibility, in its relation with centrality and monumental permanence, that remains unchanging on the surface of a rugged topography whose gaps are bridged by creative practices that rekindle both the arts and the public sphere.

On the other hand, urban art squares off with the powerfulness of symbolic creation associated to the market, to propaganda and showbiz culture. With different functions, these entities generate repertoires of images and codes that cross over, counteract and overlap one another in that environment, eventually winding up in the hands of the art in a bid to renew their meanings. On the opposite side of these media-oriented expressions, art intends to stimulate the individual’s analytical capabilities in a way whereby the spectacle ponders hallucinatory enjoyment and the celebrity of the moment. Art drives reflexive processes, not only on the artistic event, but also on a questionable status quo and on those things it can exert influence on.

Amid this universe of ever-changing relationships, the city acts as a lab, a scene and an interface. Construed as a territory of opportunities in terms of jobs, services, education, housing and higher living standards, the modern city egged on the expectations of large groups that stormed into it, overloading it and leaving evidence of how brittle its structures really are.

As a consequence of modernization ideals and its failed implementation in Latin America, the region’s cities share “predominant features that goes against the grain of modern project,” warns Garcia Canclini (1998: 40), and he adds that “instead of streamlining public life, the chaos generated by millions of cars and dozens of thousands of street peddlers prevails.” Today, the region’s so-called midsize cities and mega cities have failed to act as spaces for viably making dreams and utopias come true. In different points of their outskirt areas, people get by in extreme poverty. In addition to that, they have to deal with branded violence, insecurity, drug trafficking and fear, situations that make a dramatic dent in such human values as solidarity, affection and encounters.

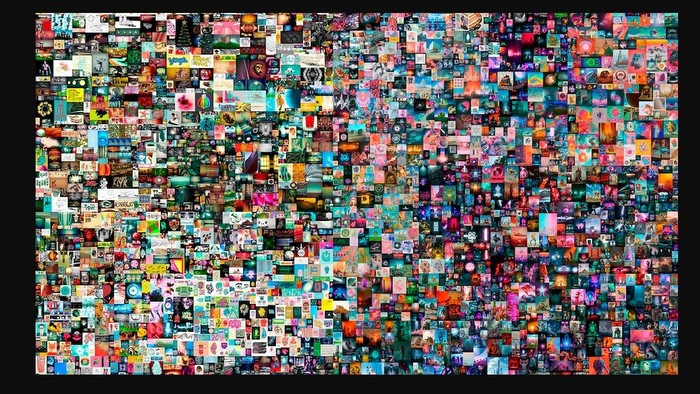

Maybe that explains why art has been putting on a clearer show in the cities, alongside a bevy of innovative incursions. As a matter of fact, it’s nearly impossible now to go reading and decoding the avalanche of images that pollutes and fragments the cityscape. In its quest for better efficiency, the new artistic practices turn to appropriation and subversion, to operations thought out in conjunction with visual, sound, musical and performing elements, to the mapping out of al alternative cartography, many times stemming from people’s ingenuity and creativeness. Bearing in mind the distracted character that goes hand in hand with the perception of the contemporary city slicker, they make use of the burg’s own language as a tool in the symbolization process.

In terms of artistic creation over the past two decades, there’s clear-cut interest in carrying through projects that can label, both esthetically and semantically, a number of outer spaces, as well as in retaking some social integration proposals that raise a few eyebrows about the neo-liberal and post-utopian condition of today’s world. Some creators cash in on the tools provided by cutting-edge technology and come up with artworks whose processes are knee-jerked in the public spaces and in the dialogue with their agents. But if there’s something really new worth highlighting within this context is the interest in addressing urban order and its layout. According to Nestor Garcia Canclini (1997: 38), “this critical look expanded from the 1980s on, at a time when de-urbanization became the main issue in most research studies on cities.”

As far as the latter is concerned, it’s important to single out a piece entitled Parachutist by Mexico’s Hector Zamora, an intervention made a few years ago in a façade portion of the modern-style building that hosts the Carrillo Gil Museum in Mexico City. Zamora symbolically moves a somewhat typical –and illegal– construction from the outskirts to that spot. She incrusts other household parameters, materials and building procedures in the formal city space in an effort to weave a paradoxical core between formal and informal urbanization –at the end of the day they coexist and complement each other.

In “Housing Unit”, seen at the ARCO Fair in 2004 where Mexico was the guest country, Zamora appealed to the disordered growth of human settlements. She used recycled cardboard boxes –a material that invokes degradation, garbage, informal economy– and the kind of rundown and rickety dwellings

commonly seen in slums across Latin America.

To a similar strategy turned Marcos Ramirez (ERRE) in his 1994 installation “21st Century”, a poor house built next to the Tijuana Cultural Center –a token of modernity in that city– that seemed it had been taken out of one of the slums along the borderline and relocated in the middle of that burg as a possible architectural prototype of the new century. Just like Zamora, ERRE laid his hands on building solutions and materials that characterize the so-called “patchwork architecture.” That explains the use of car tires to either level or mark off the lot –a recurrent procedure seen in the houses that verge on the border of Colonia Libertad (Freedom Colony). The ironic title took for granted the painstaking bickering of the new century over an array of unsolved problems.

Matching in ideal-esthetic terms with the aforesaid proposals, the “urban havens” built with the shingles of real-estate companies by the Bijari and Cachorra Co. groups, stand out. And so do the “nomadic house” by the Delborde Group, referring to the reappearance of an ancient typology in La Patagonia’s rolling architecture, currently at the service of the new immigrants. Other authors go about the damage to the republican architectural legacy in our countries caused by the real-estate market. With the help of two architects, Chile’s Angela Ramirez designed the floor of a new building as an imaginary replacement to the neoclassical edifice that today harbors the Santiago de Chile Museum of Fine Arts. Ramirez makes a contrast between the apocryphal steel-and-fiberglass structure and the preexistent-style architecture, whose predominance stands in harm’s way in the face of the intervention. Thus, she warns about the impunity of real-estate companies and the public authorities’ reckless disregard when it comes to outlining urban and housing policies to safeguard the architectural memory as a heritage asset.

Within the plurality of actions the art embarks on in public spaces, some of them are meant to lay bare the city control mechanisms and their built-in vulnerability, or just to reveal the social contrasts of the cityscape. With those views in mind, the Bijari Group has come up with the “Transverse Reality” proposal, featuring several chapters and in which street actions, the transposition of urban spaces and daily activities to the art circuit, and the presentation of audiovisuals. As part of the “Zona de Ação” project, that some time ago gathered a number of artistic groups from Sao Paolo, the Bijari Group developed an action announced under the “Estão vendendo nosso espaço aéreo” warning. In a bid to stop the predating drive of real-estate companies in the former zone of Largo de Batata, the proposal included the deployment of posters, demonstrations, a multimedia presentation and the distribution of 5,000 postcards, all that much putting together massive showbiz and activism elements into a new dimension in which the interaction codes between the social and the artistic are changed.

Daniel Lima, for his part, has embarked on projects that seek to articulate artistic groups and other associations, like “La revolução não será televisionada” and the “Frente 3 de fevreiro”, involving marginalized and conflict-stricken communities. His best interest is in those artistic processes that spread other reactions in the face of such phenomena as racism, that equally have repercussions of their own on the social and physical configuration of the urban territory. Limas has managed to use strategies and codes from the (non-institutionalized) graffiti movement and showbiz, but always from a surprising and unauthorized standpoint. In fact, the very mass show has been subjected to his interventions whenever he storms in, tossing order into complete disarray and making the audience rivet their attention on new sets of codes.

Lodged in the same interdisciplinary field is Nortec, a group attached to a much broader movement that came into being in the western U.S.-Mexican border, first with a musical view in mind following a number of successful experiments with electronic and bandstand music made in the country’s northern region. The interesting thing about Nortec, though, is not only the projection of a new music style, but also the incorporation and processing of a visual-esthetic repertoire closely likened to pop culture in northern Mexico. Its multimedia concerts are peppered with video clips, images made by graphic and fashion designers, photographers and visual artists. Without completely discarding the use of Mexican imaging archetypes, Nortec elbows itself through new possibilities in an effort to build on a kind of visual creation inscribed in the socio-cultural reality of constant border crossings and transfers.

Amid all these actions aimed at bringing the ties between art and life closer together, others have resorted to artworks linked to the community’s daily environment. Those projects involving neighborhoods, cooperatives and human groups stand for just another form of public art that, at the same time, perpetuate the primary interests the help art hit the streets. Along this seemingly anthropological inquiry line stands “Painted Walls”, an initiative developed by Monica Nador in the San Isidro neighborhood during the 7th Havana Biennial, a possible antecedent to the Jamaq project1 led by the same author together with Lucia Kohn and Fernando Lingerger, whose format meets the needs of the local residents as it chips in esthetic-utilitarian solutions and provides the community with educational services. Equally associated to this particular experience, painter Betsabée Romero has managed to readjust her symbolic vocabulary through the recycling of group-labeling objects and icons in the making of collective pieces that dignify the residents of barrios branded as marginal and violent.

Dias & Riedweg have also been working with a number of social groups since 1993 –children and teenagers from the Rio de Janeiro streets and inner cities, immigration and customs agents at the U.S.-Mexican border, street vendors of Sao Paolo, and so on– in projects capable of combining artistic creation workshops, dramatizations, inquiries, in-

terviews and public interventions. Interest in this work revolves around the notion of alternateness, while its actions tend to favor encounters and the poetic registration of those actions derived from them.

Within the kind of practices where the real and the symbolic coincide, other proposals that pierce into the establishment circuits –either in terms of information, consumption, urban transportation or money– stand out. It’s important to point out that this kind of operation proclaims itself to be in debt with the inserções that Cildo Meireles set in motion back in 1970. Following in his footsteps, Juliana Morgado has set out Brain Slicer™: useful, practical and durable, a project intended to put across a reflection on consumption among compulsive shoppers. To pull that off, she lays hands on store materials –cardboard boxes, plastic bags, etc.– and turn them into purveyors of a different kind of information, capable of undermining and destabilizing the circuit from within. Something similar comes to pass with publicity –formerly in the crosshairs of pop artists who took on its visual language– and more recently used as a source of art-oriented printing techniques and formats. A recurrent strategy consists of destabilizing the media order from the advertising billboard by inoculating disturbing elements into its structure in such a way that they wind up colliding with the traditional codes and therefore subverting the end message. That resource has bee used by German Martinez Caña when he uses the poster or the icons handled by a particular brand to refer to the causes and consequences of violence in Colombia; by Eduardo Srur when he tosses out his “harmless” bombs of colored inks over spectators in Sao Paolo in the wee hours of the morning, and by Minerva Cuevas as she blasts the dreadful situation of homeless children by means of propaganda associated to Mexico’s lottery.

It’s equally interesting to see the work of those who act from the virtual space, a public-domain area that has been exerting increasing influence on the reconfiguration of citizenship over the past decades. One of the most efficient projects in this direction has been the Better Life Corporation thought up by Minerva Cuevas. Operating from the World Wide Web, she manages to get around those mechanisms aimed at facilitating free access to a number of Web-based free services and products. Emails, on the other hand, gives this conceptual art trend a new lease on life –formerly known as mail art– that hatched quite a good deal of advocates back in the 1970s. Today, in the hands of Lazaro Saavedra, for instance, the email becomes a multiple-support format for transmitting both texts and drawings that sail outside the international circuits, spreading their reflections on power relations, the ties between art and esthetics, the situations of the artistic scene and the nation’s life, always from the perspective of critical humor.

I can’t fail to mention those creators who enhance and reactivate the possibilities of conventional genres, like engraving, by turning the city into a matrix for huge printings (the Grafito Group, for example), or by invoking sculpturing from the subversion of its own attributes (Nadin Ospina in her piece “The Walker” and Marcos Ramirez with his “Toy an Horse”). The former piece was made with non-perdurable material like an inflated ad, ready to make the rounds in any city, but without getting to become part of the identity of its many public places –quite a significant difference to the traditional statuary. In the second, the inner volume is visually and semantically nixed in the conventional bust statue, a move that panned out to be one of the work’s main messages. Other good cases in point could be the sculptural-technological hybrid created by Argentina’s Joaquin Fargas, entrenched like a guard of the climate change at the gateway of the Antarctic and in charge of passing on information about that topic through the Internet. Or just take a look at Nele Azevedo’s Minimum Monument project, consisting of small sculptures cast in ice the author puts in colorless, non-tourist, non-commemorative sites, thus disarraying the monument notion by means of the scale, the deployment location and the end intention –aimed not at perpetuating the official memory, but rather at paying tribute to the short-lived human existence.

Other proposals worth mentioning here are those conceived in keeping with the possibilities provided by the interaction among the public space, the passerby and the community, inspired in the situational derive. Others twist the beaten track for a multitude of purposes and connotations. Let’s just remember the walks of Francis Alÿs, or the dam built by Shirley Paes Leme in a street of Ushuaia during the First End of the World Biennial. The latter makes clear reference to irresponsible introduction of beavers in that territory and the serious ecological unbalance caused by it.

As to the presence of public art in visual arts events across Latin America, there’s a need to admit that over the last twenty years and from different positions and approaches, it has truly served as a topic for different curatorial proposals and discussions hovering around the not-always-efficient ways of ingraining them in its structures. The way this presence has been implemented so far in several projects worldwide calls for second thoughts about its viability in line with possible financings, authorizations and compromises that could hamstring its free and full development. Equally laudable efforts and outcomes have helped other projects remain up and around, like InSite in Tijuana and San Diego, Arte Cidade in Sao Paulo, and Puerto Rico 00, 01 and 02, as well as a number of other timely initiatives such as Multiple City in Panama and Agua-Wasser in Mexico.

Old and new purposes, as well as artistic strategies and typologies, flow together into what is now called public art, bearing in mind that their meaningfulness and functions are rethought time and again by both creators and theoreticians. In Latin America, coupled with a marked desire for deinstitutionalization, environmental upgrading and the interest in reaching out to a broader and more heterogeneous audience, new initiatives based on a kind of thinking that goes far beyond those purposes and whose actions embrace –from a conflicting perspective– the linkages and breakings both the individual and the community go through when facing off to the unstable and tangled-up urban space. At the same time, artists focus on the search of tactics that could guarantee the survival of public art, either by means of direct actions on the physical space –whether leaving his or her mark in it– or proposals that put their field of operations in other public domains through interactive and communicative mechanisms that target more the concealed and flashing side rather than the ostensible and permanent part.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Broeckmann, Andrea: “Esfera pública e interfaces de red”, en Alzado Vectorial. Arquitectura relacional No. 4, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, México D.F., 2000.

Duke, Félix: Arte público y espacio político, Ediciones Akal, S.A., Madrid, 2001.

García Canclini, Néstor: “Arte desurbanizado, desinstalaciones fronterizas”, en InSite, 1997.

____________________: “Arte desurbanizado, desinstalaciones fronterizas”, en InSite 1997. Tiempo Privado en el espacio público, San Diego: Installation Gallery, 1998.

Maderuelo, José: El espacio raptado, Mondadori, Barcelona, 1990.

Publicación anterior First Chile Triennial. Scouting the boundaries

Publicación siguiente Julio le Parc and light demystification

Publicaciones relacionadas