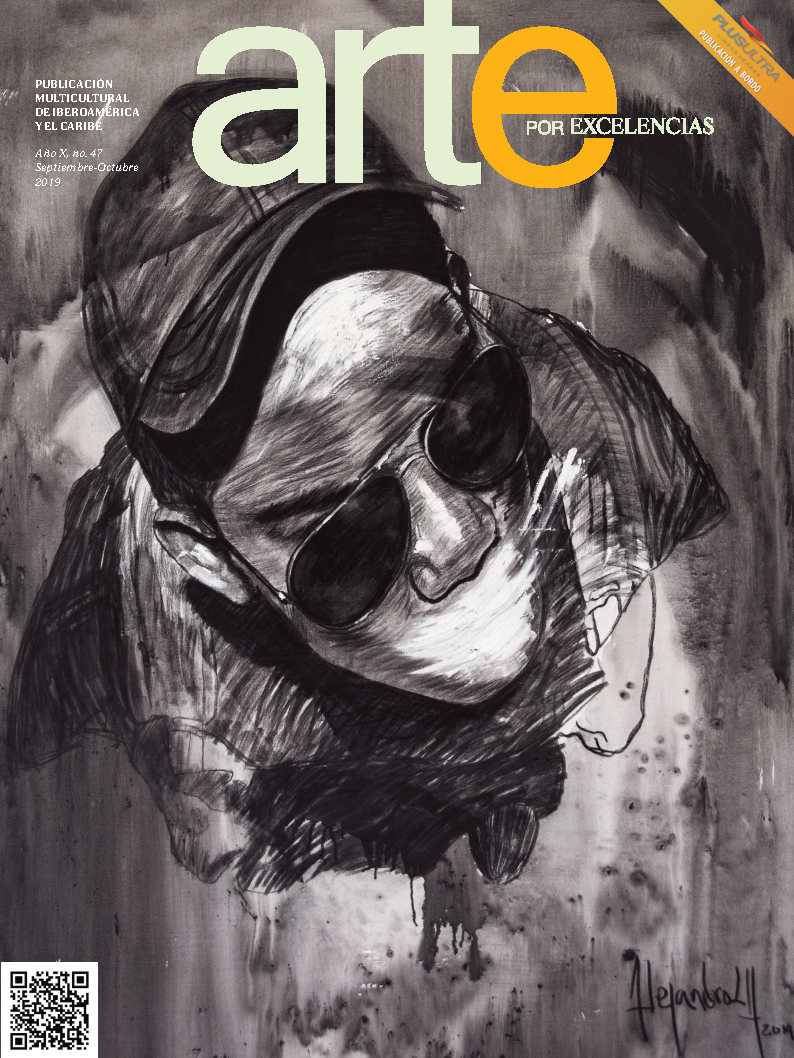

The Orí. El Òrìsà personal exhibition is just another excuse to take back on Santiago Rodriguez Olazabal’s artwork, one of the esthetic proposals that better brings together the rituals, the ceremonials and, above all, the knowledge of the African-origin religious worship that, once inserted and enrooted in Cuba, operates with the context in its intersections, on the basis of contingency, pragmatism and operational capacity.

Perhaps one of the most significant basic elements in the artist’s work is the outstanding compilation of “warnings” that fundamentally target the moral fate of the worshiper. Olazabal switches that sense and nitty-gritty objective through his poetry while he redoes a collective identity that was whipped into shape –as it has been averred every so often– on the basis of experience, tradition and memories of different origins, as well as tiny pinpointing in one large region. There must be a need to recognize, above all, that it was forged as part of a hybrid blurred by “tractions,” negation, intolerance and prejudices begotten and expressed firstly from the colonial relation system and afterwards by the inability or integrationist incapacity of the postcolonial processes, especially due to historic reasons and racial deformations found even among those for whom, as part of the State’s official policy, the new social-cultural perspectives have tried to rebuild and vindicate the scope of the different cultural universes and identities without the meddling and discriminating strategy of the “messianic civilizing model” whereby popular religious expressions and, above all, those hailing from the black continent, were labeled as “bastards.”1

The “urgency” in Olazabal’s work is humble despite, of course, the integration of the entire philosophical assumptions, the turning points in the rituals and ceremonials that engulf his whole work in a bid to legitimize and spread the ethical warnings and pierce the daily moral behavior of all men.

Santiago Rodriguez lives out oblivion, or just to put it in a different way, simply can do with vindicating religious syncretism and saving it from the realm of reminiscences and nostalgic testimonies. He dignifies it from the arts, especially with a sincere compensation of vitality and projection arrayed in a way that takes no worshipers to prove its worthiness and requires no moments of “crisis” to get by and show how deep its roots run.

Olazabal’s ingenuity, the sweeping energy of his works, the heated character, the suggestive aura of the images, or even the dramatic, intense sense that oozes out of his compositions, moves far beyond the cognitive ties with which he watches –he simply watches– unable to break free from an inexplicable supra-sensorial interaction, even when he doesn’t manage to get over the allegedly airtight symbolic universe that strips him of knee-jerk anecdote.

Like the “nuts and bolts” of the Ifá Òrìs?à cult, the texts, phrases and words in his works send a strong message of expressive, symbolic and semantic autonomy. In these cults, words replace the lack of visual representation, but the importance of the verb energizes, in the long run, the linkage with the worshiper. That’s what happens in Olazabal’s representation.

In the work “Te Amarré la Lengua” (I Tied Up Your Tongue), a huge all-white head carries in its mouth a bunch of irons, knives, sticks –real objects glued on cloth- that incarnates the representation of Ògún, Òrìsà from the Hills, whose moxie and braveness make him a winner. The suggested reading –in its ambivalence– is both subtle and smart: the tongue bears the àse, because words make us achieve or destroy a lot, even everything. Ògún is beefing up the meaningfulness of the word, though it’s also restraining imprudence, anger, the expression people wield when “damage” is meant.

The selected works for the sample overcome the asepsis of previous drawings in virtue of a highlighted conceptual vigor, of the virtuous rationality of the trade that praises ideas and the expressionism that displays an inner strength in both the work and the artist. The closed eyes in nearly all the figures reveal the power of introspection, the need to look inside and recognize our internal universe.

The image is laid out in a monumentality that can be felt in the gravity of the drawing, in the lines, the gestures, the stains, as if is were the snapshot of the very convulsive dynamics of the ritual, the sound of the words and the prayers that are part of this sacred and intimate act. Yet all this much is conceived to be assimilated from the apprehensive spirituality of the human beings only to understand that the relationship Òrìsà-man or woman is in the form of a dialogue, but is also a singular connection and a transaction in which you give and take a whole lot more than a mere material bonanza. It’s not only a coldhearted negotiation –as it’s regretfully assumed by many– that remains trapped in the immediateness of the value of any perk.

“Eja tútù meta Orí” is one of the works that moves anyone with its expressionism and representative “aridity.” It lifts us to the substantive transcendence of the EBO, a ceremony held for the purpose of feeding Orí, for the strengthening, purification, buttressing of the land and the prosperity of health.”2 The saying goes like this: “àse ebo, àse to”, characterizing the importance of this “cleansing” whereby a peculiar interaction among the deity, the worshiper and the officiants is established.

In this òrìsà-worshiper communion is expressed in the Orí, a form of energy that connects the earth with heaven. As Olazabal puts it, “it’s like entering a state of metaphysical dreamscape.” The worshiper gets involved in an act of faith as he or she seems to receive the energy and the power of the ancestors through the mo júbà of the méjì of Ifá, whose special cadence, intonation and inflections “confirm” its importance for the “completion” of the Ibori ceremony. There are no parables in this work; everything is aimed at dimensioning the sacrifice by “offering” three fresh fish to the head, as it’s evoked in the head title.

In all these works, the constant presence of hyperboles pans out to be the resource of choice for trespassing the cryptic, for making distinctive symbols and images that would otherwise remain hidden for those who know nothing about the basics of the worshiping and rituals. The end result would be the echeloning of certain readings.

Olazabal validates the timely choice of certain odu, stories and ceremonials or “works.” Thus, the piece entitled “Cabeza verde-cabeza seca-cabeza hueca” (Green Head-Dry Head-Hollow Head) pays no heed to descriptions but rather to the conceptual and iconic synthesis in a bid to capture the meat of the message. Ifa says that the tongue wants to speak faster than what the head thinks, therefore the Ifa nuts are not just nuts. Ò rúnmìlà wanted to crack some nuts and rallied all the Òrìsà because none of them was able to do so on his or her own. Only Orí cracked the nuts with his head. Since then, Orí is the top and supreme being, vital and definitive. He’s out thinking cap, our reason, our conscious. Your head guides you, but your head also gets you lost. Of course, in this last instance, “everyone carries his or her own weight,” an ironic, nearly sarcastic piece that motivates us to take a closer look at our own responsibility.

The symbolic universe of religious worshiping is overblown in Olazabal’s own iconography as he creates a new imaging in which he no doubt makes the representations that go along with the cult morphologically more complicated.

“Orí Méèrìn Layé”, an outstanding piece given the imposition of images, symbolizes the four cardinal points that support the world (the head of the cardinal points), the evocation of the creation, but also it leads to Òrun (the otherworldliness up there) and Aiyé (the earth down here). And in this conception, the virtue of Osun (Oshun, the last Irúnmóle or deity that came down the pike) to work conciliation among all the deities. That explains the use of mirrors and gilt pigment.

Olazabal is increasingly more consequent with the end use of resources, materials and components of his artworks, things that have become indispensable as so has been the insertion of matter, the object, the special “weight” and the visual energy. Like a genuine alchemist, he makes his own pigments, makes use of alloys, powders, herb juices that act as conceptual complements in his works and reinforces the sense of everything and all the parts without making any concessions whatsoever.

This versatility has allowed him to get to the realization of an installation for one specific space within the gallery. In fact, he has taken on this work as an experimental piece in which once again he accepts the challenges of his specialty and lays his hands on the emancipating nature of the installation, this time around brimming with the articulation provided by the interdisciplinary character of it, by the insertion of sound, the scenic layout and the scrolling of the text, though in a minimal sense.

Elements, attributes and symbols of Òsányìn, the mighty deity, are rendered in the Kobelofó (pot), Aweru or Tintiyero (gourd filled with beads and spruced up with feathers), the turtle shells –their favorite food– the earthenware jars that keep the well-concealed secrets of power, protection and knowledge, the Agborán (a wood-carved figure) and the nse (hanging from the walls) they protect. The smells, the leaves and the sounds belong to the mystery of the jungle innards, inhabited by the forces of all the shadows which have evoked from the darkness of the hall a strange glimpse from the spectator who clearly hesitates about the pertaining of its irruption in space while he or she suspects the piece’s sacred ambiguity.

“Los dieciséis ojos de Òsányìn” (Òsá- nyìn’s Sixteen Eyes), represented by 16 round mirrors located in a way that we can see our own steps, resemble “psychic eyes” that lead us to recognize ourselves in that inverse and identical image, as well as to rediscover ourselves in the field of understanding (òye), knowledge (imó) and wisdom (agbón) into the daily going of life.

May 2009

Publicaciones relacionadas

Obras de García Márquez para celebrar Halloween

Octubre 30, 2024

Cerrado por obras: Museo Sorolla

Octubre 29, 2024

La Mascarada llena de color y vida a Costa Rica

Octubre 28, 2024