Our access to reality is made almost always through a screen (cell phones, digital cameras, video games, DVD players, television, etc). Reconnaissance within this dynamic, in the case of marginal contexts, is usually made from states of scarcity due to the total incompatibility of our status symbols with the media globalization. In Cuba, for example, it is common to see people carrying cell phones that they only use as call receptors because their personal economies don’t allow them to afford the service. It’s like playing a game of “appearances” in which the important thing is to radiate an image and not the reality itself.

Our access to reality is made almost always through a screen (cell phones, digital cameras, video games, DVD players, television, etc). Reconnaissance within this dynamic, in the case of marginal contexts, is usually made from states of scarcity due to the total incompatibility of our status symbols with the media globalization. In Cuba, for example, it is common to see people carrying cell phones that they only use as call receptors because their personal economies don’t allow them to afford the service. It’s like playing a game of “appearances” in which the important thing is to radiate an image and not the reality itself.

The development of video art and other digital artistic expressions have won an important place in discussion forums on the island, since they promote a process of social revelation unprecedented in the history of Cuban art. Video art transfers to the world of arts thanks to copies of works that are passed around among friends and acquaintances. If performance and action art once played a key role because they mostly dealt with social issues in a moment of ideological debates; at present, video art and other technology-based trends are more interested in “private” matters. The comment on the marginal and the roots of such behaviors in the country’s reality serves to generate another story starting from current social and cultural conditions. This displacement makes certain artists become more interested in some sort of self-reference, expressed through enquiries and experimentations in their own creative process.

The case of Raul Cordero could fall within a trend that focuses on art through ludic-tone essays that emerge from the basics, equipment, functions, limitations and freedom inherent to this field. He is more concerned about qualities evocative of the plastics adventure than about possible adjacent texts deriving from social or political fields. His interests are more related to culture or anthropology. One of the most interesting lines of video art in the island was presented with his proposal “Let me tell you a video” (Déjame contarte un video)(1997), which shows a slightly ironic discourse about the challenges of marginal artists faced with fashions and styles imposed by art.

In a similar way Looking for permanence (Buscando la permanencia) (1996), was an attempt to find out or “simulate” properties of the painting (perspective, for example) within the video means. Another paradox of his ludic strategy. Hence, he managed to split his body into several temporary planes to give a feeling of depth. At that time, he still had some trouble assuming the genre due to drawbacks in production. The scarce conditions to develop a work of this type are very well-known.

In Here and There, included in the Hello/Good bye Series (1999), despite not having a narrative accent, he suggests situations related to the sense of ownership, traveling as a myth of personal realization. Without pretending to making a social report, he uses certain contextual variables that, being resolved within the video language and managed randomly rather than in a precise way, take the reflection to other levels of senses. The story takes place during the edition time. The time factor has always being a constant to take into account in the full-of-nuances discourse offered by the artist.

Reportage (1999) is perhaps one of the works from this period with the largest amount of readings about the destiny of the media in our world. At times, Cordero has been criticized for not tackling social issues in his proposals; specifically, not tackling the Cuban reality. For that reason, documenting a street fight of a marginal-looking couple, keeping to the artist’s ethic commitment to the simple representation of the social milieu, becomes a contradiction in terms. The constant agreements and disagreements of the characters, after hurling insults and yelling at each other (as a cuasi archetypal representation of the Cuban social environment) shows that it would be pertinent to discuss Raul’s understanding if his intentions were limited to “representing the reality.” It leaves unanswered the questions about what the artist should or shouldn’t address in his work.

In our conversation, he told me he doesn’t like for people to talk about his studies because he doesn’t believe they are proportional to the artist’s pedigree. Graduated from the San Alejandro Arts Academy and the Higher Institute of Industrial Design (ISDI) and having worked as a professor at the Higher Institute of Art (ISA), Cordero has always maintained a hallmark in his works. Reluctant to accept possible straitjackets of standardized points of view that usually fall into social or political remarks; he prefers to focus on the research of the creative nature itself. Although he managed to establish a convincing production through video art, during the 1990’s and early in the 21st century, studying at Graphip Media Development Centre in The Hague, Netherlands, marked him in such a way that he decided to go back to painting.

Coming closer to Rembrandt’s works and to the Dutch painting in general made him question the values of his work and he felt like he was still highly in debt with the pictorial format. He confessed that although he used the video art in his research for eight years, he used to feel tense; he didn’t enjoy what he was doing at the time. It was as if he was trying to win a place in a sped-up career where he got to enjoy a privileged position at the cost of not experiencing pleasure.

Six or seven years ago, Cordero begins to work with the painting without scorning the privileges of the new aids. Broadly speaking, his creative process changes to using the computer to make the mixture of pictorial layers and when he obtains the result he wants, he takes it to the canvas with the polyester resins he uses in his works. He employs polyester resins, at times, as a means of expression within the composition and, on other occasions to reiterate the title in the painting with dots previously mixed with oil colors.

With that aim, he uses dissimilar images within a wide range of representations that he has treasured as a result of his investigations; he seems to make the most of everything. He designs a piece of stage machinery in which opacity plays an important role: transparences, velatures, and overlapping images. One could wonder whether such interleaved texts represent a gesture of axiological questioning about the status of art or if they just respond to a cold aesthetic of impersonal topics and procedures that reminds us of the Young British Artists’ practices, made known by the end of the 1980’s. If we choose the first one, it could be an intertext showing a symptom and scapegoat of the lack of authenticity, of our flaws as an unfinished cultural project, of our ignorance and also a symbol of individual power of what creativity can achieve. That is the loophole he exploits to share with us contradictions that are not always obvious: the superfluous that can lie within the so-called sublime, which applies to any fields of modern life. In order to do so, he goes deeper into the strata of reality with delight, submitting us to a process of analysis that is not limited to making superficial or lineal approaches, but retraces and challenges the contemporary “logos”, helping us in some way to learn by questioning our own project as human beings. What else could it be Expenditure series where he stamps the calories he consumes when making a painting? The time he devotes to his project differs from images that represent certain maneuvers or exercises highly charged with concepts (launching a diving board, contortionism, roller skates race); and from others where time is spent on painting a simple inn, still life, or interior scenery, suggesting marked contrasts at times.

It is true that the artist is careful about making social speculations in his work, but it can’t be ignored that it touches in some way, though in a tangential manner, aspects related with the artist’s commitment, the challenges posed by the market and the differences between reflexive art and made-to-order works.

He even gives rise to humorous variables in his series Optional title series by offering the public different titles to choose a) Bad believer, b) Cuban decorative painting (Pintura decorativa cubana) (with a suspicious conceptual trend), c) Cuban conceptual painting (Pintura conceptual cubana) (with a suspicious decorative aspect); having us play a constant intellective game. However, if we decide that his poetic art points to skepticism and irony, but in a more ambiguous register, then there is no doubt: we are standing before an artist that just still feels in debt with painting and prefers to continue dabbling to make the most of the most traditional genre.

The scenes charged with icons that seem to not fit right with one another could speak about our “late arrival” to the modern project, our cultural unfitness, as though we lived oblivious to so many relevant events; a situation that he knows how to take advantage of as if he sought an aesthetic of uncertainty. Many of his references depend on artistic knowledge, and others, as I said before, make us laugh. For example, by placing zeppelins as if he talked about megalomaniac ambitions.

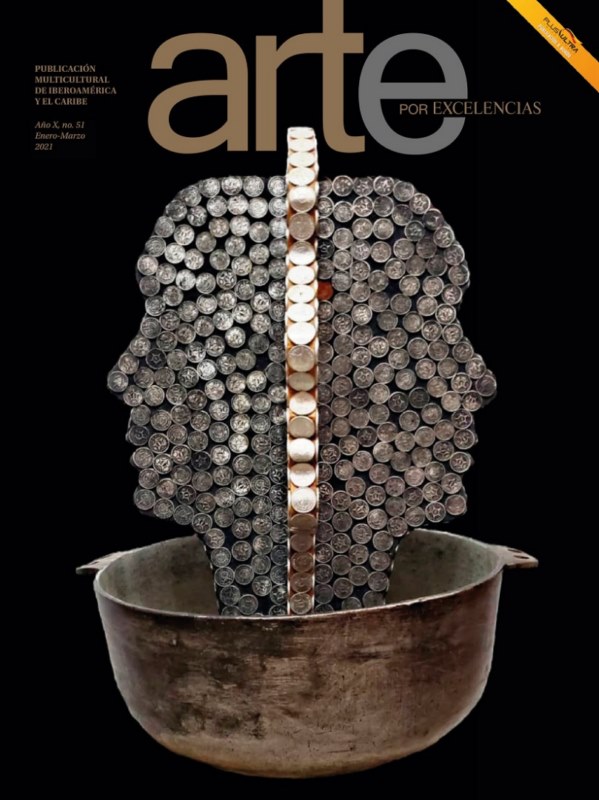

In November, the Servando Gallery hosted his exhibition Hendrickje, another exercise of “changeableness” within his work that for a long time focused on video art, and which he is considering to expand now within the paining until falling in the context of abstraction. The exhibition emerges from his admiration to Rembrandt’s work, who spent great part of his life with his maid Hendrickje Stoffels who later became his model and concubine. She assumed with a singular stoicism and boundless selflessness the economic and moral bankruptcy suffered by the greatest genius of the Dutch painting.

Cordero started to work in October 2009 on nine paintings of the same size, all of them different from each other, taking as reference classical genres of the history of painting: portrait, landscape, still life, abstraction, etc. There were no connections among them other than the fact that they all contained elements of the painting of Hendrickje Stoffels, badend in een rivier, of 1654. All nine paintings were arranged in a way that when you take an aerial picture of the whole set, it showed the image of Hendrickje as painted by Rembrandt. Does this attitude prove him to be convinced that appearances have an important place in the media world? Perhaps his decision of taking Hendrickje –who, in spite of being the cause of a legal accusation against the Dutch master on the charges of concubinage (he was married while maintaining relations with her), she was the one who spent more time by his side, who supported him the most and in return whom the painter loved the most– as an icon, can be taken as a remnant of romanticism amidst so much conceptual lucubration that can be sometimes boring or outdated. He decides, among other maneuvers, to pay tribute to the portrait, and his own attitude of laconic cynicism gives him away as he says: “I wanted to paint a monkey.” Too innocuous to be true, even more when in this version he doesn’t quote any artists or famous figures, he just had fun painting, and as if the author were annoyed by her omnipresence, he disdainfully titles the piece: “No more…”, coming from a Cuban it’s hard not to think of irony.

In “Camouflage”, he uses elements of Green and Black Orchid by British artist Gary Hume, who was part of a generation of creators that used banal images, sometimes taken from the world of publicity, in compensation to the social commitment earlier assumed by the neoexpressionist movement. The author then combines certain solutions by both trends to hide his real intentions. Behind the camouflage, if we look carefully, we can see a human face. Rembrandt painted a large number of portraits and self-portraits, and in the latter it was hard to notice his real identity. When representing himself, he usually took the time to change his looks.

One of Cordero’s hobbies is the movies and he doesn’t miss a chance to make reference to this expression. In Julie’s Diptych, he adds elements of the film Down by Law (1986), by American Jim Jarmusch, which was praised by the critics for its experimentations within a minimalist language. In one of the canvas, he introduced part of a line from the film: “Julie, what are you doing here?” and in another one: “Just watching how light changes.” The text is printed on a dim background that combines architecture and lighting, both of them are very controversial topics in Cuba.

He refers even to Spanish designer Paco Rabanne, with his well-known and iconoclastic creations with metal, plastic or paper weaves, in Beads, anther work in which the Cuban artist uses resin to resemble this sort of glass bead framework. Once again, he shows ambiguity.

Plata y Oro/ Silver and Gold is another diptych in which he takes advantage of the interventions of buildings through cuttings, known as Cuttings, which brought American Gordon Matta-Clark to fame. Likewise, he introduces in this piece a quote from his Photoglyphs, consisting on sequences of pictures of graffiti taken in the trains of New York. Cordero also makes reference to his well-known split house (a two-story house carefully cut into half). Although constantly avoiding being related with social or political comments, he bows to other predecessors who actually questioned the concept of utopia.

In a similar way, the rest of the pieces embrace elements of Oof, by Ed Ruscha and New York Street Shot, by Billy Name, respectively, because all of the work of the artist is like a test in which he questions our knowledge, expresses the intertextual character of the act of creation (although he doesn’t have narrative intentions), and he bets on the possibilities offered by the painting, convinced that the most important thing is not what but how. Let’s see Hendrickje as a tribute to the most experimental and subversive mind of the art in the 20th century, taking as focal point the painting of a woman made by an artist that makes us believe in the infinite power of creativity. This removal proposed by Cordero constitutes a challenge to our own insight, an invitation to accept that limitations don’t stem from the format used but from our own concepts regarding art.

Publicaciones relacionadas

Obras de García Márquez para celebrar Halloween

Octubre 30, 2024

Cerrado por obras: Museo Sorolla

Octubre 29, 2024

La Mascarada llena de color y vida a Costa Rica

Octubre 28, 2024