The Whitney Museum of American Art will present "Nothing Is So Humble: Prints from Everyday Objects", a focused exhibition of works drawn from the collection that highlights the creative and irreverent ways that artists have employed the ordinary objects around them to make prints. All of the works are being shown at the Museum for the first time since entering the collection. The exhibition opens on November 20, 2020 and will remain on view through April 2021.

Nothing Is So Humble, curated by Kim Conaty, the Whitney's Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawings and Prints, features the work of seven artists—Ruth Asawa, Sari Dienes, Pati Hill, Kahlil Robert Irving, Virginia Overton, Julia Phillips, and Zarina—and spans the early 1950s through the present.

The show's title comes from a proposition by the artist Sari Dienes: "Bones, lint, Styrofoam, banana skins, the squishes and squashes found on the street: nothing is so humble that it cannot be made into art." With these evocative words, Dienes described an expansive approach to artmaking that recognized aesthetic possibilities in the most mundane of subjects.

Kim Conaty remarked: "It's inspiring to witness how curiosity and care can transform familiar encounters into powerful and enthralling impressions of the world. These artists demonstrate that the forgotten, discarded, or overlooked can have important stories to tell, if we take the time to look for them."

The artists in this presentation bring distinct sensibilities and intentions to their work, but together they share an unconventional approach to printmaking. Rather than mark a metal plate or carve into a block of wood, they have worked directly with the stuff of their environments: making a rubbing from a maintenance-hole cover, photocopying a hairbrush, running nylon stockings through an etching press, even pressing a slice of prosciutto onto a printing plate. The resulting surface impressions—at once precise and abstracted—capture intimate views of their commonplace subjects that teeter between recognizable and elusive. By making visible what might otherwise be overlooked, these works memorialize the ordinary into poetic and poignant accounts of our world.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS AND WORKS ON VIEW

In early 1950s New York, Sari Dienes (1898–1992) and many of her contemporaries across a range of disciplines began to move beyond studio-bound Abstract Expressionism and to engage with the urban environment. Her formal printmaking background—including time at the renowned printing studio Atelier 17 in New York and a residency upstate at Yaddo—offered tools from which to draw and, more importantly, conventions from which to break. Dienes embraced the streets of downtown Manhattan as her studio, wielding ink brayers and large rolls of paper or Webril (a cotton-based material used in the medical industry) to capture evocative impressions of subway grates, pavement cracks, and maintenance-hole covers. In H.P.F.S. (1953), Dienes memorialized the City's found textures and utilitarian elements as if making a rubbing from a loved one's tombstone.

"An artist is an ordinary person," Ruth Asawa (1926–2013) once remarked, "who can take ordinary things and make them special." In Untitled (SF.045c, Potato print branches, purple/blue) (1951–52), Asawa transforms the most basic of pantry items—a potato—into a printing matrix that yields a luminous, rhythmic composition. Slicing one of these kitchen staples in half and carving a simple drawing into its interior, Asawa alternately applied blue and purple ink, stamping the potato onto paper to create collage-like layers made up of a single motif. Like the looped wire sculptures for which she is best known (one of which is on view currently in Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019), Asawa's print is built from minimal, repeating gestures that evoke organic forms.

In the late 1960s, upon returning to her former home and studio in Delhi after years abroad, including stints in Bangkok and Paris studying relief and intaglio printmaking, Zarina (1937–2020) became fascinated by the physical remains of earlier projects, especially the weather-beaten wood scattered around the studio. She began repurposing these leftover wood scraps as ready-made matrices, revealing the intrinsic beauty in her found materials. Rather than carve into the wood to add her own marks, she assembled the pieces into a collaged configuration that could be inked and printed directly. For the itinerant artist, who also spent time in Bonn, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, and Tokyo before taking up residence in New York in 1977, materials often stood as markers of place and time. By constructing rough architectural compositions, Zarina suggested complex relationships between home, displacement, borders, and memory—themes that captivated her throughout her career.

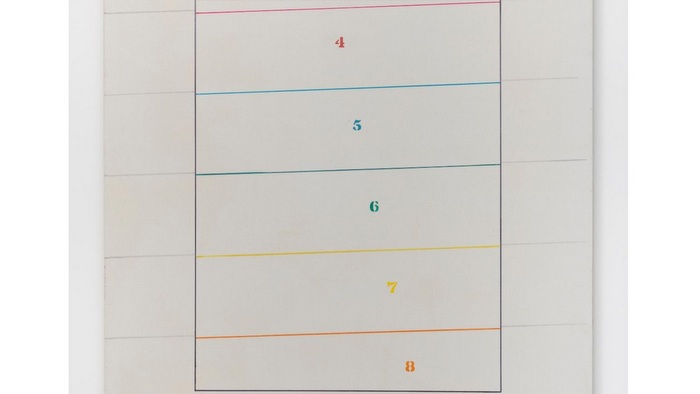

While working in her kitchen with a loaned IBM Copier II, Pati Hill (1921–2014) created Alphabet of Common Objects (1977–79), an intimate and expansive document of the everyday objects around her. Hill, an accomplished poet and author, became captivated by the aesthetic potential of the photocopier—how it recorded the unseen side of items she placed on the scanner bed, how subtle halos mysteriously appeared around the edges of objects, and how slightly opening the lid affected the opacity of the image. Positioning her images of mass-produced items like hair curlers, a mousetrap, and screws in dialogue with one another, she forged a dynamic system, which she described as a "grandiose plan of interaction."

The prints from Julia Phillips's Expanded series bring the paradoxical material qualities of nylon hosiery into visible tensions: restrictive and conforming, concealing and revealing, resilient and fragile. In these works from 2016, as well as in her cast-ceramic sculptures, Phillips (b. 1985) suggests the human form through its absence. Her direct use of hosiery—stretching and fastening it across a support, then inking and running it through a press in a modern relief process known as collagraphy—allows her to be intimately involved with the material. She encourages tears and punctures, at times sewing repairs in order to print the material again, anew. The final compositions approximate skin and allude to acts of violence against invisible bodies, conjuring histories of race, gender, and colonialism that have long occupied Phillips.

Virginia Overton (b. 1971) is a New York-based sculptor who draws inspiration from the environments in which she works. In a series of Untitled prints from 2017, Overton took the same approach, forging playful and uncanny configurations from items collected while working with Danish printer and publisher Niels Borch Jensen in Copenhagen. Over a two-week residency, she scavenged the streets, local flea markets, and the print shop itself. In collaboration with master printers, she then experimented with intaglio and relief techniques that allowed her to work directly with these foraged items, pressing objects as varied as drinking straws, wire, a discarded vial, and prosciutto from a shared lunch directly onto the printing plate. Overton's sculptures were shown at the Museum in a solo show in late 2016.

Kahlil Robert Irving (b. 1992) takes inspiration from the material accumulations of the urban environment. Here, the street itself—"the literal ground," as he describes it—is his subject. Capturing the traces of littered and discarded objects like fast-food wrappers, a cigarette pack, a crushed pizza box, and tape, Irving interrogates the street as a site of both liberation and decay, revealing the ways in which materials can carry histories of racial and class inequities. The artist is fascinated by what he describes as the "life" of objects, and he makes casts and impressions of items he collects on walks around his Brooklyn and St. Louis studios. In this work, gathered objects are collaged to the paper's surface, while other objects, like truck tires, are inked and printed directly, leaving tracks on the paper akin to skid marks. The real and the replicated are bound together under the pressure of the printing press. For Irving this unique print suggests a world of its own—the street reflecting the night sky, asphalt merging with the cosmos. The artist's work can also be seen currently in the Museum's show Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019.

Related Publications

Galerie Lelong & Co.: Pinaree Sanpitak

November 01, 2024

The Art Show: Castelli Gallery

October 31, 2024