When the gender theories are unknown, when no reading has been made, the joke seems to be the perfect way out. Feminism is more about lesbians with pent-up feelings, the interpretation of queer has to do with unresolved Oedipus characters, or the politics of manhood goes along with needs of social legitimization among homosexuals in the closet. This sounds so good when the frolicking ignorant can shed no light on the issue and things slide into lampoon and witches’ Sabbath.

In the second half of the 20th century, we learned that the subject is never abstract. Man, generically construed, stands for a far more dangerous entelechy than what it actually looks like to a naked eye. In the name of man’s dubious virtue, of comforting abstractions, the most terrible crimes have been committed, as well as the least humane exclusions and segregations. The subject always projects himself from a positioning. Better yet, not from one, but from several ones. The subject’s voice sweats directly or indirectly, a mounting of conditions whereby the cultural level and ascendency, the ethno-racial pertaining, the political creed –third parties barely exist in the mind– sexual orientation are expressed. Gender theories have taught that masculinity or feminism is a socio-cultural construction far more complex than the mere sexual identity, or biology, anatomy, physiology. Gender assumes a construction owed to learning, to the formation of the individual, the guidelines of his or her education, without ruling out the willingness of the subject, his or her sexual orientation –which also appears crossed by the experience of social confrontation, and the like. The inner self struggles between the claims and the drives of themselves and the contextual demands of the Super Inner Self. What we label as masculine or feminine is eventually run across by psychosocial and socio-cultural processes that move far beyond the inclination of the libido.

Gender theories have taught us that more than just masculinity in abstract, there are masculinities, those that are hegemonic and subordinated. Today’s struggle lies in the attempt to undermine the boundaries between the two of them, which doesn’t mean that the lines of desire are good enough to let the institutions act within the social fabric –the solid that resembles the air– and that redound as-a-matter-of-factly in both hegemony and subordination. There’s no such thing either as feminism. Even though the stance of the gender represents a political attitude –of course, there’s no need to be afraid of the term– the most lucid feminist is not precisely the one who wants to replace the patriarchal pattern for the matriarchal realm, or the one who assumes that women’s emotional and rational universe can take the luxury of discarding or attempt against the power of masculinity. Thinking of the processes of artistic culture, especially in cinema from the 1970s, the term systematizes the reflections of a discouraging feminism that probably constitutes the other great epistemological commotion following Michel Foucault’s A History of Sexuality.

These authors, in competent studies on the classic cinema –especially the black cinema– and by the hand of stabbing essays on narration as a science, have deconstructed the hegemony of the masculine way of understanding the world, installed by the patriarchal society. They have lashes out on the fallacy of narration’s universal law, according to which all stories tells us more than just an individual’s fright in his quest for the object of his desire as plenty of social, familiar and moral snags get in the way. This feminism lays bare that whatever has been disguised as “universal” has done nothing but clone a world with values of its own attached to the masculine mindset: the gathering of such attributes and experiences as travels, adventures, possessions, belongings,

conquest and domination. In that sense, these authors have turned to the glimpse at the classic cinema, the kind of spectator for whom the sublimation of women’s objectivity is achieved, rather than the quieting and gilt fetish. In the case of contemporary cinema, there are some encouraging analyses on filmmakers, like UK’s Derek Jarman or Danish Lars von Trier. Jarman set out to review the history of the British State on the basis of the relocation of the homosexual individual and the scornful critique of exclusion. However, his movies had to be misogynic. There was a complaint against exclusion that was cloning the very mechanism of segregation and was, in the same breath, generating just another hackneyed concept: the others who hate the others; a game of reflections, a refraction of experience. As far as the Danish moviemaker is concerned, we have witnessed the passage of women from martyrdom to the absolute demonization of her threat in a film like Antichrist, a misogynic treatise in which women are portrayed as psychological pincers that tweeze the males. Perhaps Lars von Trier hasn’t realized that what he’s showing is nothing by the excessive hatred and exclusion of the patriarchal society. Women pose no threat at all, that’s what Von Trier tries to portray, maybe too much driven by the guidelines of the patriarchal Super Inner Self.

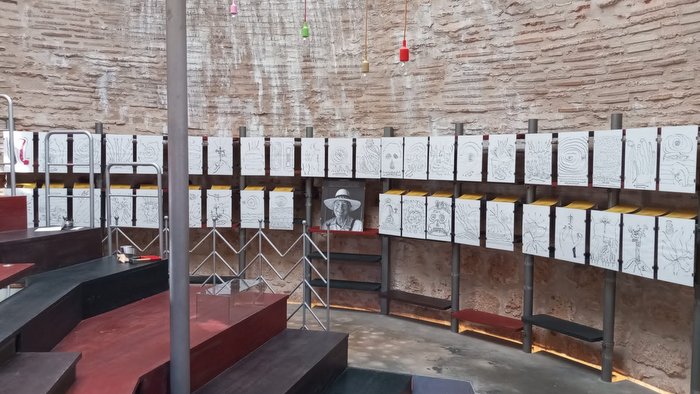

Regardless of poetic interpretations made by such artists as Frida Kahlo, Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, Jose Luis Cuevas, Robert Mapplethorpe, Rene Peña, Rocio Garcia, Aymee Garcia, Eduardo Hernandez and many others, nothing can be construed without cottoning on to the rules of the queer theory, the unveiling of the sublimations of secular machismo, the artistic use of sadomasochist trappings, the gay poetry or the parody of gay poetics, feminism, etc. The amount of gender studies conducted from the standpoint of the visual arts is still pretty slim. Perhaps the reason behind this has to do with certain abstract trend around modern and contemporary visual arts that hinges on man’s huge problems and his times. Reviews have failed to perceive –or just a little– the filter where those “big-time reflections” are siphoned away in when it comes to gender perspective. Commonly, this kind of study is socked away for arts more directly linked to the pulse of everyday life, arts of a more analogical and even more dramatic nature, like cinema, the performing arts and storytelling.

In the most recent creation of the video art, far more related to the genealogy of the visual arts than to the audio visual field, properly speaking –a situation we’re planning on dealing with in coming editions of All By Oneself– we find, especially in the art made by female artists, an intense perspective of gender. Feminist-oriented video is no stranger to female creators, that’s for sure. As a matter of fact, the feminist thinking can be seen in creators like Antonioni, Humberto Solas, Woody Allen, Almodovar, and others –squared off against the imagery of moviemakers like Martin Scorsese, whose films are mostly leaned to unraveling the masculine psychology. In Cuba, it’s been a couple of years since a video made by a man, Javier Castro, offered a complex gender perspective. In Variable Sizes, a group of women caught on tape explain the penis size they prefer. Javier was giving evidence of the isolated machismo that inhabits the mindset of Cuban women and, in that respect, was mulling over the scope of the patriarchal hegemony that eventually manages to convince even its most troublesome female interlocutors.

But there’s a group of female artists who use their videos to pry into the encouragement to feminism, not in excess, not with hateful accents, but rather with supreme intelligence. In Palimpsesto –just a case in point– Aylee Ibañez relies on the sound of a testimony on the salvage domestic violence endured by women and inserts that sound in a series of performance images created by herself, some of them striking stylized poses and stances that finally reach the possibility of sentimental morbidity. Yet she manages to touch the inner fabrics by means of cultural finesse, like in a scene when the artist’s irony or dramatic consciousness work on the developments commented by the victim. Marianela Orozco has caught on tape an array of performances in which censorship or existential anguish does not affect each and every individual in the same way. However, that anguish is suffered in a very special way when is endured by a woman. In Way, Marianela parades in her underwear and high heels on a 130-foot-long

piece of felt cloth only to get wrapped around in that same cloth a few minutes later, picked up by a man and a woman and whisked away in a vehicle. This work is a brilliant piece of irony showing the two extremes as far as behavior toward women is concerned: the worshipping of the glamorous, desirable object, the runway girl, and the fiery annulations that trample on her. The artist works out the situation with a wallop-packing parabola related to the kind of subordination historically reserved for her gender. That’s something that in the case of Balance is far acuter and more nerve-racking: the creator tries to resist, to cling to the balance between two compressing bars. Is that pressure for staying afloat more dramatic than the best sports exercise? Could it be the same in today’s world, before the eyes of men? Marianela’s video performance seems to let us in on the fact that pressure on her head is far more formidable, far more painful than the one any man could carry on his shoulders: repression is twice as much hurtful then.

Humanism used to claim for men’s values in an ecumenical sense and it used to slither into the setup of depicting just one kind of man –white, western, straight, nearly Arian. The transit thinking and artistic imagery woven for centuries is sticking to its guns –and this image I’m resorting to could either be balletic or military. It’s squared off against the politics of segregation and disguised subjugation. People must love baseball and ballet, jump from the flower to the saffron. Enough is enough when it comes to hegemonies!

Today’s socio-cultural individual is multiple, performance-oriented and transversal. Let’s take a look, for instance, at Maria Regla, a physician in the morning, a biker in the afternoon and a transvestite at night. Maria Regla cuts herself out as a liberal islet under an excluding sky in a historically macho city. Pointing a finger at Maria Regla is the liberating way of saying: “I’ve got no problems; I’m straight like an arrow. The problem is there, and is called Maria Regla.” And then, at 3:00 in the morning, that same punisher goes out to ask Maria Regla for sexual favors, because a black man like him, well built and tall, and dressed like a woman, makes people wonder he’s probably hung like a horse too. And then it’s worthwhile to be Maria Regla’s woman. The social punisher wants to be Maria Regla’s woman and for pulling that off he’s got the perfect alibi: Maria Regla is dressed like a woman.

Today’s contemporary art takes care of Maria Regla. But rather than that, it takes care of the genuine transvestite, the pretender, the mounting of masks and conditions that marks the behavior of the contemporary individual whose compositional richness is a far cry from straight arrows or closed identities. Why contemporary societies, why men and women in different ways are so hooked on the big horse? Today’s art seems to delve into that, with a perplexed glance and trapped between powerlessness and certainty, as if it were shaking off the old ghost of our beloved Freud once and for all.

Publicación anterior A CURATOR’S QS AND AS

Publicación siguiente Writings of Argentinean Art: Between Researchers and Curators