The San Sebastián Festival is devoting its latest classic film cycle, co-organised with the Basque Film Archive in collaboration with the Japan Foundation and the Etxepare Basque Institute in the framework of the Euskadi-Japan 2023 program, to the director Hiroshi Teshigahara (1927-2001), a key figure in Japanese cinema in the 1960s thanks to a series of experimental poetic films and his extensive collaboration with the writer Kobo Abe. The only one of his films to be distributed in Spain, the acclaimed Suna no onna / Woman in the Dunes (1964), sums up that period and Teshigahara's style really well.

Teshigahara was born and died in Tokyo and first studied Fine Arts and made his debut in the mid-1950s in the field of the documentary short. Interested in all the trends in Western cinema that had shown the resistance movements during the 2nd World War, to be precise, in Italian neorealism and the French films of that period, he formed part of a kind of club called Cinema 57, where documentaries that often couldn't be seen in commercial cinemas were screened and discussed. This clear interest in documentary cinema would considerably influence him when he moved on to making fictional full-length films.

His first short, Hokusai, is from 1953, and his first feature film, Otoshi-ana / The Trap, from 1962. Between these two dates, Nagisa Oshima –the Festival devoted its retrospective to him in 2013–, Seijun Suzuki, Shohei Imamura, Susumu Hani, Yoshishige Yoshida and Masahiro Shinoda, representative directors in the various trends of the Japanese New Wave, had already made their first films. Teshigahara played a more incidental role in this movement and had a less of an international impact, despite winning the special jury award at Cannes for Woman in the Dunes and being nominated for the Oscar for best director and best foreign language film for this same movie. However, in one way or another he was right at the heart of the conceptual turmoil that turned Japanese cinema upside down through new subject matter and ways of filming.

He had a productive partnership with Kobo Abe, who wrote the script for The Trap and the adaptations of the three novels that Woman in the Dunes, Tanin no kao kao / The Face of Another (1966) and Moetsukita chizu / The Man Without a Map (1968) are based on, which were the filmmaker's key works. Abe also wrote the script for Ako, an episode in the collective film La fleur de l'âge / Les adolescents (1964), four stories about adolescence filmed by Teshigahara, Jean Rouch, Michel Brault and Gian Vittorio Baldi.

His final films, Rikyu (1989) and Go-hime / The Princess Goh (1992), were historical works. He also shot films for television and constantly made short, medium-length and full-length documentaries. He made two films about the Puerto Rican boxer, José Torres, one about the Swiss sculptor and painter Jean Tinguely and a film about Tokyo in 1958. However, his best-known documentary is Antonio Gaudí (1984), an excellent approach to the figure and work of the Catalan modernist architect.

As well as being a filmmaker, Teshigahara was a master in the Japanese art of flower arrangement (ikebana). From 1980 until his death, he ran the Ikebana Sogetsu school, which had been founded by his father, and he published the book The Art of Ikebana (1997). He was married to the actress, Toshiko Kobayashi, who he only directed in one film, Sama soruja / Summer Soldiers.

At the 71st San Sebastián Festival, which will be held from the 22nd to the 30th of September, all of this relatively unknown director's films will be screened. Two of his films have taken part in the Festival in previous years: Woman in the Dunes –in the "Ashes and Diamonds" cycle in 1985– and The Man without a Map in the "Japan in Black" retrospective organised in 2008. The cycle will be complemented by the publication of the book by Inuhiko Yomota, Avant-garde chronicles. Conversations with Hiroshi Teshigahara, translated from Japanese by Daniel Aguilar.

Violent Italy. Italian crime cinema

On the other hand, the San Sebastián Festival will be devoting its 2024 retrospective to what are known as poliziotteschi films. Entitled Violent Italy. Italian crime films, the cycle in the 72nd Festival will include a selection of films from a genre that provided an accurate portrayal of the country that even today still needs to be reexamined from a contemporary perspective.

After surviving the years of fascism and the post-war period, the Italian crime films seemed to achieve its canonical form with the film by Pietro Germi Un maledetto imbroglio / The Facts of Murder (1959), the first one that moved away from imitating French noir to establish a model of its own that was to open up a genuine golden age for the genre. It was to evolve in sync with the politics and society of the country from then on: if the Italy of the economic boom shifted it to urban settings and reflected the early onset of organized crime and criminality, the May 1968 unrest, which was particularly vicious in Italy, meant that it would take a political turn thanks to directors like Francesco Rosi or Damiano Damiani.

The Golden Palm and the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film that Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto / Investigation of a citizen above suspicion (Elio Petri, 1970) won seemed to mark the end of the gender, but far from it becoming ossified, this would open it up to new variations: if the orthodox crime film was to continue thanks to directors like Fernando Di Leo, mafia movies would take it along previously unknown paths. After winning the Silver Shell at the San Sebastián Festival, La polizia ringrazia / Execution squad (Steno, 1972) would open up the potential of the poliziottesco, that reflected the turmoil caused by the emergence of terrorism depicted in accordance with the parameters established by the American generation of violence.

Source: San Sebastian Film Festival

Related Publications

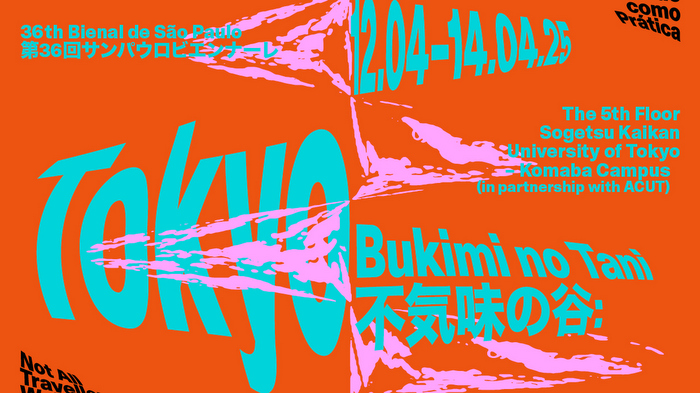

The last Invocation of the 36th Bienal arrives in Tokyo

April 08, 2025