In the mid 1990s, the random encounter between Fernando Paiz and Ramiro Ortiz on a plane unleashed a number of developments that triggered a sea change in Central American fine arts. As businessmen and art collectors, the conversation took them to the complex scenario their countries were going through and to the lack of development opportunities for local creators. In Guatemala, the Paiz family boasted a longstanding tradition of support to the arts, basically by means of a foundation that used to organize the national biennial (since 1978) and that was at that time the only one of its kind in Central America. Nicaragua, on the contrary, didn’t have any similar experience or structure to rely on.

Following that encounter in 1996, the Ortiz-Gurdian Foundation came into being in Nicaragua. Ramiro Ortiz and Fernando Paiz managed to bring in impresarios and cultural managers from all across Central America to be part of an unprecedented regional initiative. The Empresarios por le Arte organization was founded in Costa Rica; the Fernandez Pirla Foundation started out in Panama; in Honduras, the initiative is joined by Bonnie de Garcia, who at the time was the owner of the Portales Gallery; and in El Salvador, Olga Vilanova worked closely with the Banco Proamerica. This year can be penciled in as a key date in the advance of a regional effort spearheaded by businesspeople, art collectors, curators and cultural managers, let alone as a moment that should be assessed much deeper when it comes to writing the history of corporate social responsibility towards the arts in Central America.

To top all that off, the first Central American Isthmus Biennia was held in 1998, at the Miguel Angel Asturias Theater in Guatemala City. Juanita Bermudez began the coordination efforts for the Nicaraguan foundation’s cultural program, thus becoming the enthusiastic force that in a short period of time made people and entities function like clockwork all around Central America. But a region trapped inside itself, battered by a multitude of conflicts, marked by educational drawbacks and marred by a mediocre artistic education system, was having a hard time in trying to read discourses that had already become paradigms in art circuits worldwide. Having been born as a Painting Biennial was a logical consequence of the reproduction of quasi-ancestral systems. Growing in the midst of an artistic community that badly needed to be “up to date” and demanded further support and changes from its structures, posed quite a challenge this Biennial is still trying to work out. In addition to the acclaim, the event has counted on the accurate review of curators, experts and artists who believe they have managed to put across art-legitimizing mechanisms and reach out to artists who haven’t responded to the new discourses of the contemporary arts. As a regional event, this biennial hasn’t yet been able to be in sync with the theoretical and practical outcomes of other entities that have popped up in Central America. Yet this is an entity that deserves to get the credit when it comes to dealing with the region and its artistic scenarios.

National and Central American biennials have witnessed the complex discussions the regional art has been through in recent years. In their bid to make room for artists, they have not only supported their legitimization, but they have also become a reflection of the profound lack of phase between institutions and contemporary creation.

While this Central American scenario was being whipped into shape in the 1990s, the Ortiz-Gurdian Foundation was taking strides in Nicaragua, thus becoming a benchmark for the rest of the regional efforts that were under way.

As a foundation that saw the light of day within a family that shared a passion for the arts and a deep-rooted willingness toward art collection, its heritage has always been its backbone. Around that core, structures have been clustered, cultural promotion programs have been defined and citizen proposals have been advanced.

Since the 1960s, the Nicaragua Central Bank had begun to amass Nicaraguan artworks, setting an example for other banks across the nation. During the nationalizations occurred in the 1980s, those collections got scattered. A major collection of painting, sculpture and Pre-Hispanic artifacts is currently lodged at the Hugo Palma Ibarra Foundation.

The collection at the Ortiz-Gurdian Foundation could be labeled as one of a kind in the country given its consistency and number of pieces, but above all, for the willingness of its founders to step out of the local turf and come up with an assortment that actually reflects the development of the national art and is able to rub elbows with all major artistic movements worldwide.

Today, only a handful of Central American collections can boast such a collection laden with regional contemporary art and, at the same time, showcase both the growth and articulation of a system that allows for the creation of countless networks in the regional and international scenarios it has been bound to play in.

As a result of its commitment to the country, the foundation picked the city of Leon as its venue of choice. Standing at 56 miles from Managua, Leon is the nation’s second-largest city, historically attached to poet Ruben Dario, who eventually died there. Leon is one of the cities with the most cultural and architectural values.

The Ortiz-Gurdian family hails from this city and its members are determined to pay permanent tribute to it by engaging in actions for the preservation of its cultural and architectural heritage. The restoration of the Via Sacra of the Leon Cathedral –it includes huge oils on cloth painted in the early 20th century- is a good case in point.

A good chunk of the foundation’s collection is now at the disposal of both Leon’s residents and visitors. It’s housed in two lovely colonial mansions that have been thoroughly refurbished.

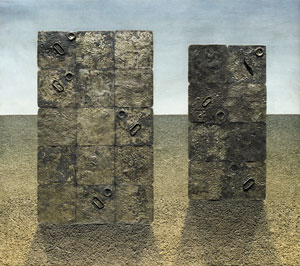

At Norberto Ramirez’s house –the first property where the collection was mounted- there are 252 artworks (paintings, sculptures and pre-Hispanic ceramics, mostly hailing from San Juan de Oriente. In 2010, the Derbishire House opened with a grand total of 54 pieces of contemporary art, including several installations and videos. The exhibit is also made up of prizes and honorary mentions doled out at the Nicaraguan biennial, plus a number of Central American pieces that artists from other countries in the region have displayed in regional events.

A tour around the foundation’s facilities sheds light on the development of the Nicaraguan and Central American arts in the 20th century and in the course of the 21st century. But feeding mostly on acquisitions made at the national and regional biennials, the foundation helps the public to understand the way whereby an event like this models perceptions, dictates parameters and tones down processes that take place in the local artistic scene under regional common denominators.

In recent years, the region’s contemporary art has gained spaces and projections that have been taken on by the Ortiz-Gurdian Foundation as catalyzers of inner reflective processes when it comes to deciding on new acquisitions. This is mirrored in an institutional will to leave former paradigms behind and the nonstop quest for top-quality works that could match harmonically with pieces that were purchased before in a bid to cotton on to a complex scenario like Central America’s.

The main challenges the foundation has been faced with have been the same that hit it at the onset. From a private glance, how can you make a major and long-term contribution to the public space? How can you make a major contribution to the contemporary art in a region riddled with so many urgent needs? How can you create spaces for dialogue and discussion among artists in an environment marked numerous social conflicts and that in the course of recent years has seen violence take center stage in the daily life? What long-term strategies could come up from the creation of national and regional collections that protect the heritage of nations where the preservation of cultural values and assets is not a top priority for the local governments?

The Ortiz-Gurdian Foundation has a huge responsibility in its hands, a responsibility to help answer those basic questions, especially in a region in which institutions are weak, resources dwindle and the political willingness in terms of heritage protection and the development of more opportunities for national artists is virtually nil.

In a zone splintered by wars and chipped away by violence, this foundation has responded by strengthening its national commitment, eager to put its smart money on regional alliances, distribute its resources all across the region in the form of sponsorships in an effort to keep biennial events running. What’s more, quite recently the foundation has opened up to new ideas from Central American and international sages, engaging in talks that will hopefully pay off in the near future.

Related Publications

How Harumi Yamaguchi invented the modern woman in Japan

March 16, 2022

Giovanni Duarte and an orchestra capable of everything

August 26, 2020